Oil prices dropped back on Monday 23 October 2023 after diplomatic efforts over the weekend to try to prevent the conflict between Israel and Hamas from spreading, including aid convoys being allowed into Gaza.

The price of a barrel of Brent crude oil, the North Sea benchmark, for December delivery fell as low as US$91.08 on Monday morning, down by more than a dollar, or about 1%, following the weekend closure of markets. West Texas Intermediate, the North American grade also used as a global benchmark, fell by 1.2% as low as US$86.83.

But that was yesterday. Oil prices rose in early Asia trade on Tuesday 24 October 2023 (today), recovering some of the previous day's losses, as investors remained nervous that the Israel-Hamas war could escalate into a wider conflict in the oil-exporting region, causing potential supply disruptions.

Neither Israel nor Palestine are significant fossil fuel producers, but analysts are concerned that supplies from other countries could be affected if fighting spreads further through the region. Israel has been bombing Gaza in response to Hamas’s attack on civilians on 7 October, but it has so far not launched a promised ground invasion into the territory.

Vandana Hari, founder of oil market analysis provider Vanda Insights, told Reuters:

"There is some relief in the oil market that Israel is holding off on a planned ground incursion of northern Gaza to negotiate a release of hostages, which opens up a window for diplomacy. A ground siege is seen as a potential trigger for widening the Israel-Hamas conflict into the Middle East region, the factor behind crude’s risk premium over the past fortnight."

Things were very different on 18 October - less than a week ago. Oil prices rose. The WTI crude oil price was up 2.4% to US$88.72 a barrel. The Brent crude oil price was up 1.9% to US$91.60 a barrel.

One commentator from the Motley Fool wrote that the conflict may lead to a surge in oil prices, especially if Iran becomes directly involved in supporting Hamas, as this could lead to global supply disruptions. He said a spike in oil prices would "add to inflation, keep interest rates higher for longer and add to the risk of recession".

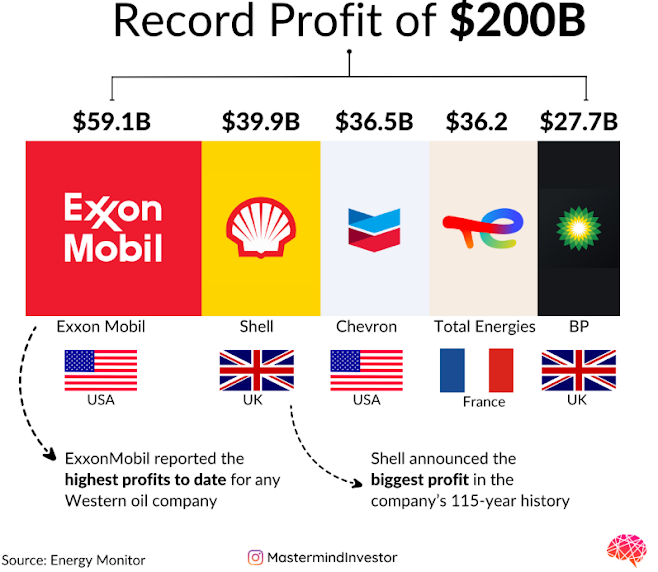

There is strong recent evidence to suggest that extraordinary oil profits can be made from conflict. The AMP chief economist points out that oil prices rose last year to a high of $US123.70 on the back of the war in Ukraine. This was their highest level since 2008 when they peaked at $US145. Russia's war in the Ukraine helped oil giant Saudi Aramco Post record an historic US$161 billion profit in 2022 with sanctions limiting the sale of Moscow's oil and natural gas in Western markets. Aramco's results mirror the huge profits seen at U.S.. French and British oil giants:

The Middle East’s oil and gas exports could still emerge as collateral damage if the ongoing conflict engulfs the region. Market observers expect that the US may soon toughen its sanctions on exports of oil from Iran, a major player in the commodity, due to Tehran’s close links to Hamas and Hezbollah.

Robert Ryan, the chief strategist at BCA Research, said there was a one in four chance that Iranian oil output could fall by a 1m barrels a day as a result of tougher US sanctions. He assigned the same odds to a slump in Russian oil output for the same reasons. This could lead to oil prices of $140 a barrel next year, according to Ryan. However, the impact of these sanctions could be eased if Saudi Arabia – which is restricting its oil output – were to increase its exports to help steady the market.

Dr Neil Quilliam, an expert in Middle Eastern energy policy and geopolitics at Chatham House said, “The one thing that could really shift the price was if the conflict spreads.”

Quilliam said: “There’s no shortage of oil supply, it’s about getting that oil supply to the market. The real concern, the material concern, is the security of the Strait of Hormuz.”

The Strait of Hormuz in the Gulf is responsible for the transit of more than 20% of the oil consumed globally and a third of the world’s seaborne gas shipments, making it a vital energy artery for the global markets. If Iran sought to block the route this would have major implications for Europe’s supplies of gas from Qatar, the world’s top exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and a longstanding backer of radical Islamist groups including Hamas. About 16% of Qatar’s exports were sent to the EU last year, making the country Europe’s second-largest source of LNG after the US. These supplies are considered crucial after the end of pipeline gas imports from Russia last year.

Oil tankers pass through the Strait of Hormuz, through which 20% of the world’s oil and one-third of its seaborne gas passes. Photograph: Hamad I Mohammed/Reuters

“It is unlikely that [the strait] would close but [military] activities in this area would be enough to push the price of oil very high for a short time at least,” Quilliam said. “It’s a well-rehearsed conversation and well-rehearsed eventuality for the leaders of many western nations.”

Saudi Arabia is the region’s most powerful fossil fuel player and the de facto leader of the Opec+ oil cartel – the group responsible for calibrating global oil market prices by carefully controlling output.

Saudi Arabia is now producing about 9m barrels of oil a day, according to the International Energy Agency. The agency estimates that Iran and the United Arab Emirates both produce more than 3m barrels of oil a day. Russia, a key ally of Opec+, produces about 9m barrels of oil a day.

For these nations rocketing oil prices would bring rich economic rewards, but only to a certain point, according to Quilliam. Once prices move significantly above $100 a barrel the high cost of energy can cause economic activity to slow and dent demand for oil. This could provide an incentive for Saudi Arabia to increase its production to rein in runaway oil market prices.

Before the attack Saudi Arabia and Russia confirmed that they would continue to hold back more than 1m barrels of oil a day from the global market until 2024 in order to shore up oil prices, which had begun to flag due to worries about global economic growth. If needed, the pair could reverse this decision if a global oil price shock threatened to erode overall demand.

For both energy companies the stakes are high. For Joe Biden, rising oil prices could spell defeat in the US elections next year, according to Ryan. For Russia, higher oil prices are vital to shore up the Kremlin’s coffers as it continues its war against Ukraine.

Biden’s attempt to broker a normalisation of Saudi-Israeli relations before the Hamas attacks might have seen the kingdom agree to US calls for an increase oil production, but the plan now risks being derailed. The US has moved two aircraft carriers into the eastern Mediterranean to deter Iran or Lebanon’s Hezbollah, both allies of Hamas, from getting involved in the conflict.

In the last 50 years or so, it is difficult to think of a time when so many dangers from so many directions could each spiral out of control so quickly as is now occurring in the Middle East, centred on the Israel-Hamas War. For the global energy market, the closest approximation to the situation is the 1973 Oil Crisis. From this, inferences can be drawn as to what may happen to oil and gas prices in the short-, medium-, and long-term. Then OPEC members - plus Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia - began an embargo on oil exports to the U.S., the U.K., Japan, Canada and the Netherlands in response to the U.S.’s supplying of arms to Israel during the "Yom Kippur" War.

As global supplies of oil fell, the price of oil increased dramatically, exacerbated by incremental cuts to oil production by OPEC members over the period. By the end of the embargo in March 1974, the price of oil had risen around 267 percent, from about US$3 per barrel (pb) to nearly US$11 pb. This, in turn, stoked the fire of a global economic slowdown, especially felt in the net oil importing countries of the West. The oil embargo marked a fundamental shift in the world balance of power between the developing nations that produced oil and the developed industrial nations that consumed it.

However, from this point the U.S., under the guidance of Henry Kissinger - who served as National Security Advisor from January 1969 to November 1975 and as Secretary of State from September 1973 to January 1977 – began to roll out its new Middle East policy aimed at ensuring that it and its allies were never again held hostage by Middle Eastern oil producers. In practical terms, this meant the U.S. appearing to be on the side of various elements of the Arab world but, in reality, seeking to exploit their existing weaknesses to set one against another.

But now we have Iran, which came into existence in 1979 and thinks that “Israel is an abhorrence- not just because of its existence as a state, but also because it is seen as the primary tool by which the U.S. seeks to extend its influence across the Islamic world of the Middle East, so [Iran] it has everything to gain by manipulating this war [between Israel and Hamas] into something much bigger,” a senior source in the E.U.’s security complex said.

“The timing of this - 50 years after the 1973 Yom Kippur War - was not just symbolic of that, but also a signal for the next 50 years, in which Iran wants to see a Middle East without Israel or the U.S., with itself at the centre, and it was important that it was done before Saudi Arabia signed a relationship normalisation deal with Israel,” he added.

Although there is a flurry of diplomatic activity taking place to avert the Israel-Hamas War widening out, on 16 October 2023 Iran’s Foreign Minister, Hossein Amir Abdollahian, warned that its regional network of militias would open “multiple fronts” against Israel if its attacks continued to kill civilians in Gaza. It seems highly likely that the first new front would be a full activation of Hezbollah in Lebanon, to Israel’s direct north; a 100,000-strong very well-equipped fighting force funded and trained by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) that dwarfs the fighting capabilities of Hamas in all respects. Israel has already stated that its mission is to “annihilate Hamas” and that to do so it will launch ground operations into Palestine for as long as it takes to do so. Additionally, over the weekend, Israel’s Minister of Economy, Nir Barkat, said that if Hezbollah fully joins the war then Israel would “cut off the head of the snake” and launch a military attack against Iran. A third front could also be opened by Iran, using its own IRGC and proxy militant forces stationed in Syria, to Israel’s northeast.

The potential for oil and gas prices to spike is considerable if the conflict does indeed widen out. Reductions in supply from any of the major OPEC suppliers – let alone all of them at once, as might be the case – would be extremely difficult to compensate for, although there are plans in place by the West to attempt to do so. Emergency gas supplies from Qatar appear likely to continue under most circumstances, which would alleviate some short-term price pain in the West, as they did after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. Plans are also in place to extend the easing of sanctions on Venezuela seen on 18 October, according to the E.U. source, with the country’s crude production averaging around 770,000 bpd in September. Additionally, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said on 12 October that it is “ready to act” if the Israel-Hamas War escalated to hit oil supplies in the region. As has been seen before in times of dramatic oil price rises, the agency can coordinate the release of emergency oil stocks with each IEA member country. Each is obliged to hold oil stocks equivalent to at least 90 days of net oil imports and to be ready to respond to severe supply disruptions affecting the global oil market. This said, OPEC+ controls around 40 percent of global crude oil supplies.

But against all this is the eventual decline in oil consumption due to electrification of vehicles. Global oil demand is set to reach a new record high this year, with over 102 million barrels consumed every single day, almost half of it by vehicles.

So far, the growing fleet of electric cars, vans, trucks and buses has displaced just a sliver of demand – 1.5 million barrels of oil per day in 2022. But batteries are on the march, and BloombergNEF is now predicting peak demand for road fuel isn’t that far off, arriving in 2027.

“A combination of EVs, fuel efficiency and shared mobility is knocking down demand for road fuels,” said David Doherty, head of oil and renewable fuels research at BNEF. “This decline gets exacerbated post-2030.”

Oil consumption displaced by EVs rises to over 20 million barrels per day by 2040, according to BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario, which models a market-led energy transition that assumes no policy changes. That is more oil than the US consumed last year.

Demand for road fuels peaks at 49 million barrels per day in 2027. “From then on, demand begins to decline structurally, reaching 35 million barrels per day by 2040,” BNEF said in its most recent outlook.

The demand for gasoline and diesel for road transport has likely already risen as far as it’s going to go in the US and Europe, while demand in China is set to peak in 2024. Demand in other major consuming countries like India starts to decline later — in the 2030s.

Market interventions could materially alter the speed of this transition. A higher oil price for instance makes EVs that much more competitive compared to a conventional combustion vehicle, and prices have just hit their highest level for the year.

The concerted push by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to elevate the price of oil up is yielding consequences it might not enjoy.

But for the next few years there may be a lot of economic pain, globally, as oil producers continue to maintain, if not exceed, their profits with the knowledge that an end to their extraordinary profit stream is in plain sight. And that, most unfortunately, may result in many more thousands of deaths, injuries and suffering in the Middle East than have occurred to date.

Comments

Post a Comment