Australia’s schools, universities, and vocational institutions are slowly being reshaped—not by educational priorities, but by defence budgets. This is not happening through a broad public mandate or informed debate. Instead, a potent mix of federal underfunding, defence industry lobbying, and government ambition has created fertile ground for the militarisation of our education system.

The result is what some now refer to as Australia’s own Military-Industrial-Academic Complex (MIAC)—a nexus of arms manufacturers, government departments, and corporatized universities that increasingly aligns education with defence interests, particularly those of foreign arms giants.

While the public is told this pivot will build “sovereign capability” and ensure national security, the deeper motivations are more transactional: lucrative contracts for multinational weapons companies, quick wins for governments seeking jobs and growth headlines, and a lifeline of funding for universities starved of public support.

From Public Institutions to Defence Incubators

Australia’s university system has been steadily corporatized over the past two decades. As federal funding was stripped away, institutions turned to international student fees to plug the gap. When COVID exposed the fragility of that model, universities were left scrambling. In that vacuum, the defence sector moved in.

US military and defence corporations have ramped up their presence in Australian higher education, with defence research grants rising from $1.7 million in 2007 to over $60 million by 2022—just one year after the AUKUS deal was announced. That deal, which promises $368 billion in nuclear submarine spending, has become a gravitational centre for education policy as universities pivot toward military-aligned STEM programs and defence-industry partnerships.

This shift is not just visible in the labs and research departments. A Times Higher Education report praised Australian universities for helping the government “build social licence” for AUKUS. That’s code for: help sell the public on a generational military spending spree. University leaders, such as those from the Group of Eight, now proudly tout their “defence capabilities” and alignment with the goals of the AUKUS program—including training a nuclear-capable workforce.

Militarism in the Classroom

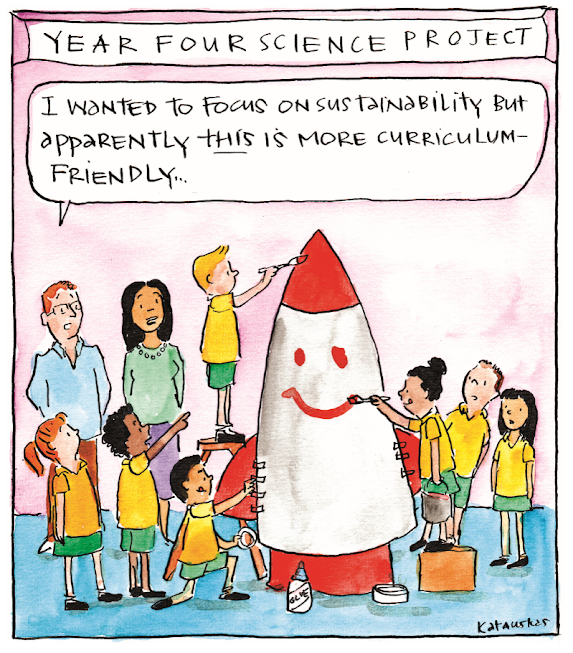

It doesn't stop at tertiary education. New research by the Medical Association for Prevention of War has uncovered that 35 weapons-linked STEM programs were active in Australian primary and secondary schools in 2022, a sharp increase from the year before. Many are branded with corporate logos like Lockheed Martin or BAE Systems and deliberately target girls and students in regional areas. Some materials use toys or cartoon characters to make weapons manufacturers look like friendly innovators, rather than agents of war.

This trend risks tilting STEM education away from desperately needed areas like environmental science, climate adaptation, and health innovation, and toward the logic of the battlefield. What we risk fostering is not a generation of engineers and scientists solving the world’s greatest challenges—but one trained to build, maintain, and normalise the machinery of war.

The Australian Education Union has sounded the alarm, particularly around how defence programs in schools tend to gloss over the dangers of nuclear technologies and frame military work as uncritically positive. The implicit goal isn’t just workforce development—it’s cultural normalisation.

Geopolitical Dependency, Not Sovereignty

At the strategic level, this alignment does not increase our sovereignty—it compromises it. By accepting funding and technical dependencies from the US Department of Defense and weapons firms like Raytheon and Northrop Grumman, Australia is being drawn further into an interoperability trap.

Rather than designing a defence strategy suited to our geography and security context, we’re spending public money to become a convenient extension of the US military-industrial base. At a time when Washington’s foreign policy is increasingly erratic, and its political system deeply polarised, our educational and industrial alignment with American defence goals looks less like strategic partnership and more like geopolitical subservience.

Some of the technologies being developed under this model—including autonomous weapons systems driven by AI—pose grave ethical and legal questions. Yet there’s little space for critique in a system where funding dictates research agendas. The more dependent universities become on arms industry grants, the harder it becomes to speak out against the implications of this dependency.

And we’re already seeing that chilling effect. Universities have cracked down hard on student protests against Australia’s silence on Gaza. Academics who critique Israel’s military actions—or question AUKUS—face reputational risks and institutional pressure. The price of funding is silence.

A Choice, Not a Destiny

It doesn’t have to be this way. Australia is not fated to become an annex of the US defence economy. We are a geographically isolated, politically stable, resource-rich country with a world-class research and education sector—when it’s properly supported. We don’t need to turn schools into recruitment grounds for weapons contractors to be safe or prosperous.

Instead, we could be investing in a sovereign, independent research and manufacturing capacity focused on climate resilience, regional cooperation, and peacekeeping. That would not only be more aligned with our long-term security interests, it would also be more in tune with the values most Australians want to see reflected in their institutions.

So far, neither major political party has shown much willingness to debate the implications of this militarisation of education. Perhaps that’s because it works so well—for them. It delivers jobs, funding, and headlines. But in the long run, it may cost us far more: our independence, our ethics, and our capacity to think freely about the future we actually want.

It’s time to ask, loudly and publicly: Is this the direction we choose, or the direction we’re being pushed?

Comments

Post a Comment