The 26%

lift in profit rubs against economic warnings issued by the banking sector

earlier this year, as lenders continue to profit from a period of

fast-rising interest rates felt most acutely by mortgage holders and

small businesses.

In August

2023 we learned that Commonwealth Bank (CBA) axed another 88 jobs in Sydney,

Perth, Brisbane, Melbourne and Canberra, as part of a restructure, impacting

221 roles. It came off the back of the major bank posting a record $10.2

billion profit earlier in August, up 6 per cent on last financial year. That

round of cuts followed 251 redundancies made in July 2023.

Later this

week it is estimated that we'll see profits of around $7.8 billion for NAB, and

$7.6 billion for ANZ.

There is no

doubt that further hiking of interest rates to

meet a 2-3% inflation target will serve to enhance the financial sector, not

consumers doing it tough.

Today Australian households have been slugged with a 13th interest rate rise since May 2022 after the Reserve Bank today hiked the cash rate 25 basis points to 4.35% – a 12-year high.

The rate rise will add roughly $100 to monthly repayments for a standard mortgage of about $600,000

The news

that Westpac has announced an annual profit of $7.2bn for 2022-23, up 26% on

2021-22, will not surprise the millions of Australian families dealing with

higher mortgage rates.

Westpac

achieved this result even though, for most of the year, many households were

still benefiting from fixed-rate mortgages at low rates, which are only now

expiring. It seems highly likely that next year will be even better for Westpac

and the other big banks. They can expect to set new profit records after a long

period of low interest rates and relatively weak profits.

Westpac’s massive profit should also not surprise the Reserve Bank of Australia. In June this year, the RBA published a discussion paper looking at the impact of interest rates on bank profitability, which starts with the observation “there is widespread empirical support that lower interest rates are associated with a decline in banks’ net interest margins” (that is, the difference between the banks’ own cost of funds and the rate they charge to borrowers).

The RBA plays down this finding, arguing that banks may find ways to maintain profitability in a low-interest environment. But as far as ordinary households are concerned, it’s the margin between the return on savings and the cost of borrowing that matters.

It’s easy enough to see that higher interest rates help bank profits and harm borrowers. But interest rates go down as well as up. If the RBA were a neutral umpire, managing the economy to maintain stability in a way that benefits all of us, we could be comforted by the idea that the ups and downs will balance out in the long run.

But the RBA is far from neutral. Like other central banks, it is committed to an inflation-targeting regime based on the idea of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (Nairu), also called the “natural rate of unemployment”. This is, supposedly, the unique rate of unemployment consistent with low and stable inflation. As the Labor government’s employment white paper recently observed, the Nairu has several shortcomings as a measure of full employment. It evolves over time, is difficult to measure and does not capture the full potential of the workforce.

The Nairu-based inflation targeting regime serves to enhance the power and prestige of central banks, and of the financial sector as a whole. On the other side of the coin, the inflation-targeting regime has been part of the process by which the wage share of national income has been pushed down over the last three decades. What’s good for the RBA is not necessarily good for Australian workers.

The conflict between the interests of the RBA and the demands of good economic management is starkly illustrated by the push for a rapid return to the 2-3% inflation range.

The 2-3% target range has never been supported by serious economic analysis. It was chosen in the early 1990s by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (initially as a precise target of 2%). The target was a political compromise, seen as the lowest rate of inflation that could be achieved and sustained without risking a deep recession.

At the time, New Zealand was seen as a star performer in the cause of neoliberal reform. The prestige of the short-lived New Zealand miracle led central banks around the world to adopt the same framework.

Since the advent of zero interest rates in the wake of the global financial crisis, it has become evident that the target was pitched too low. Economists ranging from Olivier Blanchard (the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund) to Paul Krugman have pointed out that a 4% inflation target would give more room for interest rate policy to stimulate the economy without hitting the zero lower bound.

In the recent review of the RBA, this issue was raised. But rather than address the substantive issue, the response (echoed by RBA supporters in the media) was that such a change would reduce the RBA’s “credibility”. Other things equal, a more credible central bank is a good thing. But in choosing how much to sacrifice to preserve this credibility, it’s evident that the institutional interests of the RBA are likely to be placed ahead of those of households facing higher mortgage rates or workers who risk losing their jobs.

With the RBA further rate hike today (7/11/2023), the rapid increase that has already taken place will continue to work its way through the system. The brief period of near-full employment we have recently enjoyed will come to an end, at least if the RBA is successful. And, in all probability, Westpac’s profits will continue to rise.

Update: 15/11/2023: All four of Australia's largest banks have posted substantial profits for the 2022-23 financial year. Commonwealth Bank made $10.2b, NAB $7.7b and ANZ and Westpac $7.4b each, according to recently published annual reports.

In all four cases, the profit was larger than last year. Why are banks so profitable?

Interest rates

The simple answer is that all four banks have benefited from higher interest rates.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has been 'raising interest rates' since May 2022 to discourage borrowing and spending, motivated by a desire to slow down the rate of rising prices (inflation).

When we talk about 'raising interest rates', what we actually mean is that the RBA is increasing the 'cash rate' — the rate it charges banks for short-term loans.

The RBA hopes banks will 'pass on' this higher rate to its customers.

However, it is up to banks whether they do so.

In general, Australia's largest banks have been more willing to pass on higher rates to borrowers (e.g. mortgage holders), and less willing to pass on higher rates to savers.

Banks make money from the interest they charge borrowers and lose money by paying interest to savers, so this decision has boosted their profits.

The numbers

All four banks charge higher rates to borrowers overall than they offer to savers.

For NAB and ANZ, borrowing rates are about 1.7 percentage points higher. For Westpac and CBA, they are about 2 percentage points higher.

'Percentage points' is a direct comparison between two numbers — so, for example, it might mean a borrowing rate of 6% and a saving rate of 4%.

All four banks increased the size of the gap between borrowing rates and savings rates in 2022-23.

In all four cases, this resulted in over $1 billion of extra 'net interest income' — that's the difference between interest received from borrowers and interest paid to savers.

For all four banks, this extra income accounted for a significant portion of the spike in profit.

Recall that the US is Australia’s largest direct investor, with a deep investment history that has embedded US investment in Australians’ day to day lives. That investment is A$1.5 trillion with the highest levels of investment in mining and quarrying (32% of total), real estate and finance and insurance (13% in both), manufacturing (11%), and wholesale and retail trade (6%).

For example, US companies Vanguard, State Street and BlackRock (the "Big Three") are among the largest shareholders in Australia’s largest company (“the Big Australian”) the BHP Group. Vanguard and BlackRock also appear among the largest shareholders in Australia’s second-largest company, Commonwealth Bank.

The top 10 shareholders of Atlassian (5th largest in Australia) are all from the United States with the largest being Vanguard. Vanguard is also the largest shareholder in Woodside Energy (6th).

The list is too long for this paper, but note that Westpac Banking Corporation (WBC), which the second-largest bank in Australia, has the BlackRock Group, as its largest single shareholder. The largest single shareholder in Rio Tinto is the BlackRock Group, and so the list goes on. Of course, many of the largest shareholders of Australia’s top 100 companies that are not already described as United States entities may themselves be wholly or partially owned and/or controlled subsidiaries of United States entities.

The top 24 Australian companies with significant Vanguard investment of just one of its funds (Vanguard Investments Common Contractual Fund) as at December 2022 is listed below in descending financial value:

What a surprise! The list includes all four of the major Australian banks! U.S. investors must rub their hands together with glee every time the RBA hikes interest rates with poor old Australian mortgage holders footing the bill.

But it doesn't stop with the banks, unfortunately. Recall skyrocketing petrol prices (used as an excuse for every business to hike prices - especially the major supermarkets which, surprise, surprise are also making record profits)? Here's where they figure in the equation: right behind mortgage interest charges hikes:

Earlier this year the Australia Institute released research that showed that corporate price gouging, and the associated record profits generated by it, were a far more potent driver of Australia’s inflation crisis than modestly rising wages. It’s not demand that’s driving these increases, its mega profits. This is profit driven inflation, plain and simple. The production costs of petrol have not changed nor has demand, which, if anything, has fallen due to the increasing take-up of electric vehicles. The price paid is artificially determined by oil=producing countries deliberately reducing their supply.

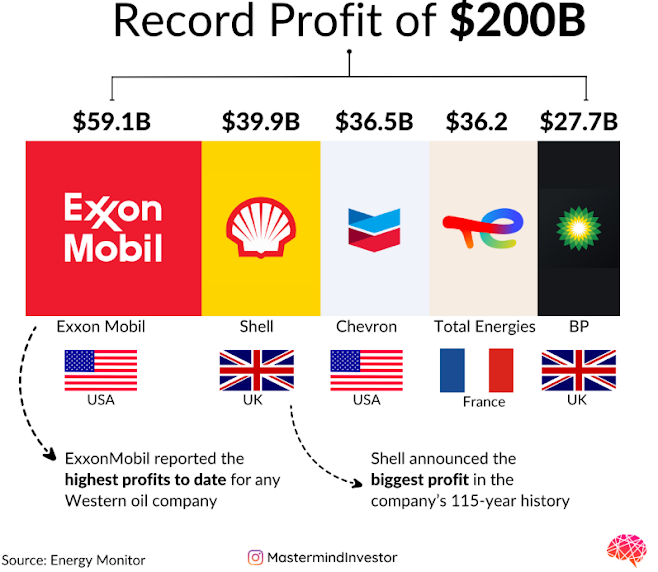

So, who are these oil companies that are so obscenely profiting?

Of course Exxon Mobil's and Shell's largest shareholders include the "Big Three" Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street Corp. Both Vanguard and Blackrock are also amongst Chevron's and Total Energies largest shareholders and Vanguard Group Inc is the largest individual Chevron shareholder. BP's largest shareholders include State Street.

Looking down the list of price gougers takes me to insurance companies. As an example, this year, IAG, Australia’s top general insurer, posted a net profit of $832 million after tax, up a staggering 140 per cent on the year before. Major shareholders: Vanguard. Again.

And let's not forget utilities: the energy companies. Origin Energy, one of Australia’s biggest energy providers, recorded profits up 83.5 per cent on the year before, with a net income of more than a billion. Origin’s profit can be put down to the doubling of its gross profits on gas and nearly tripling it on electricity. In other words, Origin’s gross profits are attributable to price increases rather than units sold. Major investors in Origin Energy? Our old friends Vanguard and State Street, again.

So thank you RBA: your contribution to the profits of US investors at the expense of ordinary Australians is applauded.

And I'm just thinking, surely some of those US investors pay a bit of tax on their profits, don't hey? Vanguard certainly tells its investors that they do.

So that's a good thing, isn't it? But wait, what are those taxes spent on?

U.S. military spending reached US $1.537 trillion in 2022 - even before the current Israeli conflict. Paid by taxes. On profits. Derived from price gouging ordinary Australians. Australia's entire GDP is only $1.675 trillion US dollars in 2022

And the biggest recipients of that military spending? Obviously, to the largest military contractors: In 2022, the largest Department of Defense contractor was Lockheed Martin (major shareholders Vanguard and BlackRock), with a contract value of about 46.21 billion U.S. dollars. Raytheon Technologies (major shareholders Vanguard, State Street, BlackRock ) was the second largest contractor that year, with a contract value of around 26.13 billion U.S. dollars.

OK, so let's see if we can follow the money through to individuals.

Starting with BlackRock. Laurence D. Fink is the CEO and co-founder of BlackRock. According to Forbes, the net worth of Larry Fink is believed to be over $1 billion, with a sizable amount originating from his ownership of 0.7% of BlackRock. While his remuneration has fluctuated throughout the years, he is frequently ranked among the top 20 highest-paid CEOs in the world. BlackRock's President, Robert S. Kapito's estimated net worth is approximately $469.54 million.

Mortimer (Tim) Buckley is chairman of the board and CEO/President of Vanguard. His estimated net worth can lie between 60-75 million USD. His annual package is estimated to be around 15-25 million USD.

State Street's CEO/President and Chairman is Ron O'Hanley whose estimated net worth is at least $29.6 Million dollars as of 15 August 2023.

But these are just the executives. The big money is with the investors in those funds. The United States has the highest number of billionaires in the world. According to Forbes, nine out of ten of the richest people in the world are US citizens. As of April 2023, 372 billionaires in the United States made their fortune through the financial sector including hedge funds, investment banking, and private equity investments.- Elon Musk: Tesla CEO and "X" (formerly Twitter) owner Musk leads the billionaire pack with a net worth of $247 billion. Tesla's Top 3 Largest Institutional Shareholders are:

- The Vanguard Group (222.48 million shares of Tesla, accounting for nearly 7% of Tesla’s stock as of June 30, 2023, according to Nasdaq. It was up from 217.85 million as of 31 March 2023.

- Blackrock: As of the end of June 2023, Blackrock held 185.89 million shares in Tesla, making up 5.8% of Tesla’s outstanding shares.

- State Street Corp: As of June 30, 2023, State Street Corporation owned 104.11 million of Tesla’s shares valued at $20.54 billion, making it Tesla’s third-largest institutional shareholder, according to Nasdaq’s data. State Street Corp.’s holding makes up 3.27% of Tesla’s outstanding stock.

2. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos with $155 billion. Amazon's Top 3 Institutional Shareholders are:

- Vanguard Group which owns 712.07 million shares of Amazon. This represents about 6.9% of all outstanding Amazon shares. Vanguard clients can invest in Amazon stock through the company's Consumer Discretionary ETF (VCR). Amazon is the largest holding and accounts for 19.9% of the fund's portfolio.

- BlackRock which holds 594.72 million shares of Amazon This accounts for 5.8% of all outstanding Amazon shares. Amazon stock is the largest holding in the iShares U.S. Consumer Services ETF (IYC), comprising 13.9% of the fund.

- State Street with 36.27 million shares of Amazon in its portfolio. This is about 3.3% of the company's outstanding shares. State Street's Consumer Discretionary Select Sector Fund (XLY) provides investors with access to Amazon stock, holding 31.74 million shares or 22.67% of its portfolio.

3. Warren Buffett Net Worth: $123.1 billion.is a major investor in Berkshire Hathaway whose largest holdings are in:

- Apple Inc. (AAPL) with their other largest shareholders including Vanguard Group Inc, BlackRock Inc,

- Bank of America Corp (BAC), with their other largest shareholders Vanguard Group Inc, BlackRock Inc., State Street Corp

- Chevron (CVX), with their other largest shareholders Vanguard Group Inc, BlackRock Inc., State Street Corp

- The Coca-Cola Company (KO), with their other largest shareholders Vanguard Group Inc, BlackRock Fund Advisors; and

- American Express Company, with their other largest shareholders including Vanguard Group Inc, BlackRock Inc., State Street Corp.

Seeing a bit of a pattern here?

- The richest 1% own almost half of the world’s wealth, while the poorest half of the world own just 0.75% In fact, they have acquired nearly twice as much wealth in new money as the bottom 99% of the world’s population.

- 81 billionaires have more wealth than 50% of the world combined

- 10 billionaires own more than 200 million African women own combined A staggering figure considering there are just over 714 million African women in existence.

- Extreme wealth and extreme poverty have seen a sharp simultaneous increase for the first time in 25 years. The World Bank estimates that due to the pandemic, the poorest 40% experienced income losses that were double the losses of the richest 20%.

- The poorest countries are spending 4 times more repaying debts (often to wealthy private lenders) than on health care. This despite the fact that it is also the poorest countries that struggled to purchase and roll out COVID-19 vaccines to fight the pandemic.

- The richest 1% own almost two-thirds of all the world’s new wealth. Since 2020, for every dollar of new global wealth gained by someone in the bottom 90%, one of the world’s billionaires has gained $1.7 million.

- A billionaire emits a million times more carbon than the average person. This is while, according to Oxfam, they’re the most likely to funnel their money into polluting industries, such as fossil fuels.

- Billionaires are collectively earning an estimated $2.7 billion a day…post-pandemic, and during a global cost-of-living crisis.

- Food and energy companies more than doubled their profits in 2022.In stark contrast, the World Food Programme estimates that 824 million people went to bed hungry every night in 2022. Shareholders saw most of the profits, with Oxfam estimating they received a collective pay out of $257 billion on average.

Read About It

The rich

get richer

The poor get the picture

The bombs never hit you when you're down so low

Some got pollution

Some revolution

There must be some solution but I just don't

know

The bosses want decisions

The workers need ambitions

There won't be no collisions when they move so

slow

Nothing ever happens

Nothing really matters

No one ever tells me so what am I to know

You wouldn't read about it

Read about it

Just another incredible scene

There's no doubt about it

The hammer and

sickle

The news is at a trickle

The commissars are fickle but the stockpile

grows

Bombers keeping coming

Engines softly humming

The stars and stripes are running for their own big show

Another

little flare up

Storm brewed in a tea cup

Imagine any mix up

and the lot would go

Nothing ever happens

Nothing ever matters

No one ever tells me so what I am to know

You wouldn't read about it

Read about it

One unjust, ridiculous steal

Ain't no doubt about it

You wouldn't read about it

Read about it

Just another particular deal

There's no doubt about it

(Midnight Oil)

Comments

Post a Comment